How many times have you shot video with your trusty DSLR only to find the footage is out of focus or to have the camera shut down because its overheating? Would a “real” cinema camera solve all your problems? Here is the first in a series of articles by Ben Long about making the transition from a DSLR to a cinema camera. –Sonja Schenk

by Ben Long

With a couple of pending video projects, I’ve decided now is finally the time to make the jump from digital SLRs to a “cinema” camera. If you’ve ever shot video with a DSLR you probably already know my reasons for the switch: I want better ergonomics; I’d prefer better low-light capability, and I’d like to be able to shoot an interview without having to stop every ten minutes. Or to shoot over the course of an hour or so without worrying about my camera overheating. Simply put: I’d like to work with a camera that was actually designed for shooting video.

The Three Types of Video Cameras

These days, you have three options for shooting video. There are traditional video cameras (this category covers everything from home video cameras to “ENG” or “electronic news gathering” cameras). Traditional video cameras have continuous autofocus, auto iris, electronic zooms, and ergonomics specifically designed for shooting video. At the higher end, they’ll have such video production essentials as XLR audio inputs, built-in ND filters, and waveform monitors. Higher-end cameras will also feature image controls familiar to video engineers – pedestal, gain, and knee controls, for example. They also usually use fairly small image sensors and will lack interchangeable lenses.

Traditional video cameras, like the Canon XA11 shown here, range in size from handheld camcorders to shoulder-mounted news gathering cameras. All offer ergonomics designed for video shooting.

The DSLR video “revolution” brought a new class of camera to the video producer. With their larger sensors, DSLRs offer the ability to shoot with shallow depth of field and in lower light, while their interchangeable lenses provide framing and composition options that aren’t possible with regular video cameras. DSLRs yield a price/performance ratio that was previously unheard of in the video production realm, and it would be churlish to complain about the limitations of these cameras. Properly kitted out DSLRs provide an astonishing level of production capability in a small, incredibly affordable package.

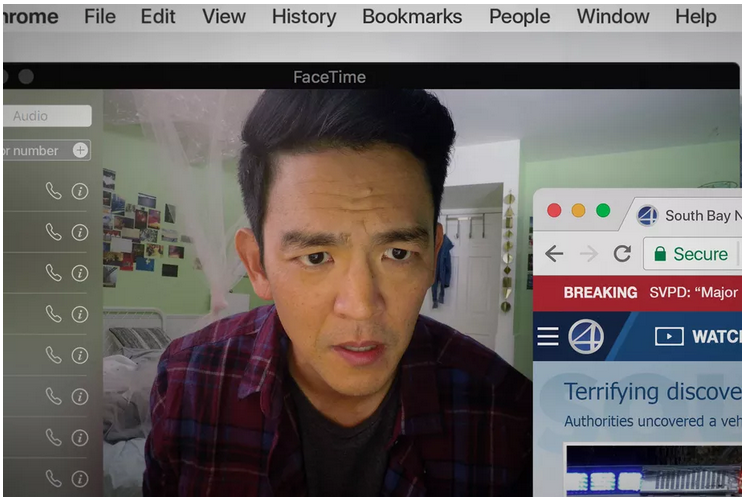

While DSLRs, like the Canon 5D, can shoot extremely high-quality video, their physical design makes handheld shooting difficult and lacks features that experienced video professionals rely on.

But there’s also a third camera option. “Cinema” cameras such as the Black Magic Ursa Mini and Canon’s C-series video cameras are specifically designed for shooting video, but use larger sensors and interchangeable lenses like a DSLR. They truly provide the best of both worlds – the video-specific features you need from a dedicated video camera and the image quality and lens flexibility of a DSLR. Once upon a time, cinema cameras started at $20,000 just for the body. The price has dropped dramatically and high-quality cameras are now available for just a few thousand dollars.

Cinema cameras such as this Canon C100 sport large sensors and interchangeable lenses, like a DSLR but with ergonomics designed specifically for video shooting.

Cinema cameras come with usability questions that straddle both video cameras and DSLRs. They require you to think more like a cinematographer than a videographer. If you have a still photography background you shouldn’t have any trouble making the switch to a cinema camera.

This is the first in a series of articles wherein I will take you through my process of making the switch from shooting video with a DSLR to shooting with a true cinema camera. Along the way we’ll cover choosing a camera and lenses and discuss how to translate what you already know into the world of cinema video cameras.